For three months, I didn’t open Figma. Not once.

The icon sat there on my dock, judging me with its colourful smugness, while I lived in terminals and IDEs like a digital hermit who’d traded pixels for code (and prompts). Then one day a terrifying thought crept in: had I become an engineer?

After some soul searching, the answer, mercifully, was no — but the doubt lingered like over-brewed instant coffee. This wasn’t just professional paranoia; it was part of something bigger.

The boundaries that once defined our work are dissolving faster than the debate about naming your layers (now that Figma does it for you).

Three forces reshaping creative work in the age of AI

To understand what’s happening to design, and most knowledge work, we need to recognise three forces reshaping how we work:

First, the lines between specialist and generalist skills are dissolving. Specialists can continue to go deeper without becoming isolated; generalists can stretch even wider without losing their core identity. It’s a paradigm shift that makes even confident professionals question what their role means.

Second, the barrier to creating functional things has collapsed. Making is no longer the differentiator — discernment is.

Third, our tools are more powerful than ever, but they demand deeper understanding to use well.

These forces aren’t happening in isolation. They’re interwoven, and the rules of professional identity don’t apply anymore.

Force 1: The great skill convergence

Scott Belsky calls this “the collapsing talent stack,” which sounds like our careers are suffering structural failure. The neat boxes we created to measure our performance, are now historical curiosities, relics from when work could be neatly categorised.

Here’s what’s really happening: if you assume we’re all operating on T-shaped skill profiles (or any shape with a x-axis and y-axis for that matter), then AI has made both directions of movement significantly more viable.

Generalists can extend further across the top of the T, without sacrificing depth, while specialists can dive deeper down the stem without alienating themselves from the broader system.

Take the visually-obsessed product designer. They can now refine border radii and shadows to their heart’s content while AI fills their gaps in user research or front-end code.

Or the data-driven PM, who is desperate to see their analyses come to life in a prototype — AI bridges the gap between their SQL mastery and an interactive, user testable concept.

The key point: you’re no longer trapped by knowledge gaps. AI is a translator between domains, letting specialists think like generalists and generalists act like specialists.

It’s not about everyone becoming the same. It’s about becoming more yourself — while still playing nicely with others.

Force 2: The fundamentals filter

Here’s where the democratisation fairy tale hits a wall. Yes, AI has significantly lowered the barrier to make things, but access to tools doesn’t provide the judgment needed to use them effectively.

You can generate code and chat casually with AI as if you’re ordering coffee. However, you can’t rely on casual interactions to achieve good outcomes. That requires a solid foundation: a deep understanding of the craft and the ability to recognize what “good” looks like.

For designers, this means having and continually developing taste — the elusive skill to differentiate between functional and delightful, technically correct and emotionally resonant. It’s about understanding why one shade of blue feels just right, while another feels cheap.

This isn’t snobbery; it’s the reality that judgment comes from sustained practice and exposure. AI can offer you a thousand options, but only human experience can identify the one worth keeping.

Many will settle for technically competent but spiritually empty “slop.” However, great work still demands that ineffable human filter.

Side note — this might sound like gatekeeping from someone protective of hard-won experience, but here’s the twist: AI-native designers can develop this judgment, this thing we all pretend to understand, faster than ever before. Today’s tools can compress decades into months, but only if you’re willing to put in the reps.

Force 3: The power–complexity paradox

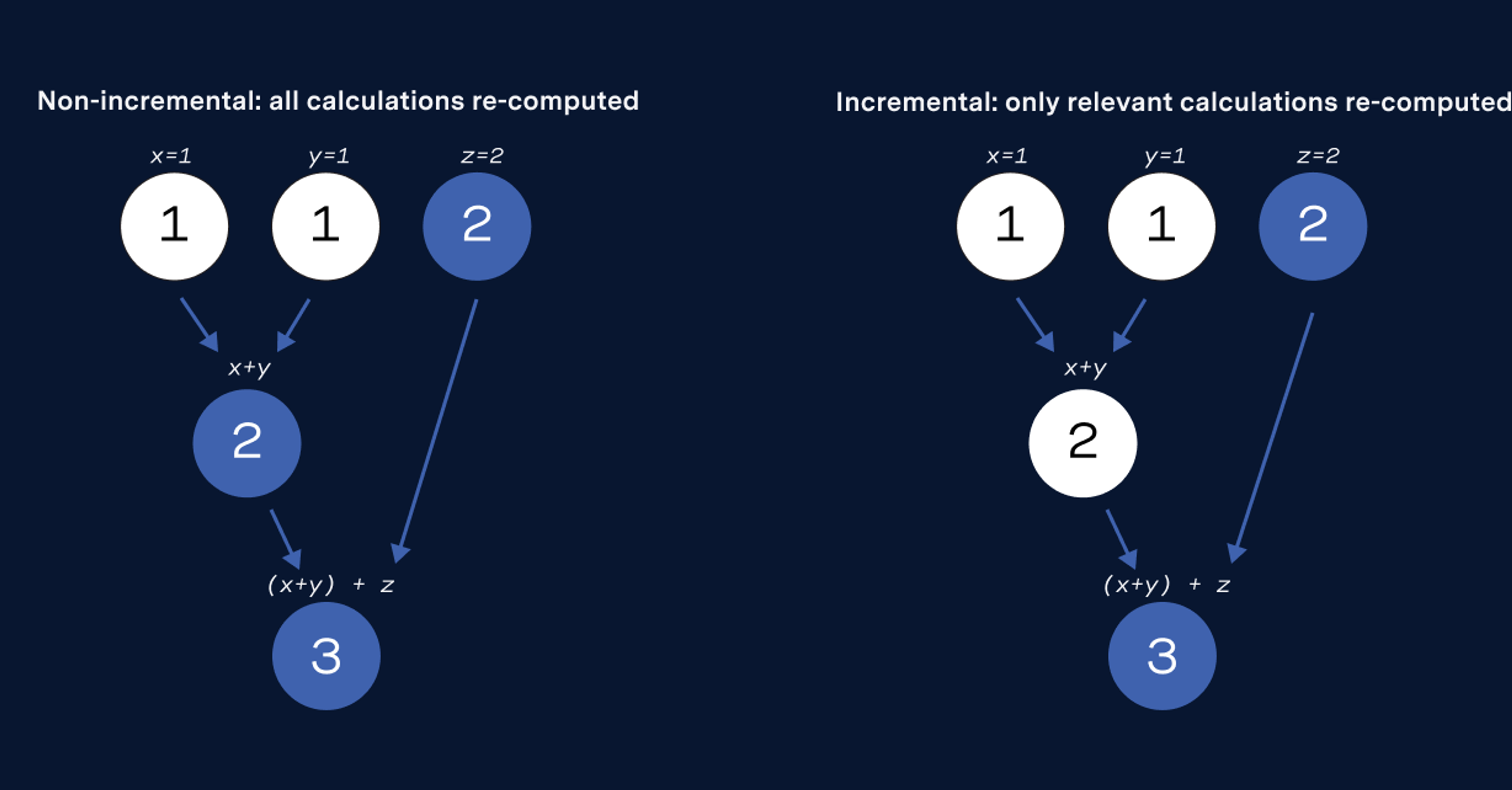

Here’s the strangest contradiction of our moment: increasingly powerful tools require increasingly deeper understanding to use well.

It’s like being handed a Formula 1 car. Yes, you could sit in it and have a general idea of what to do. However, without practice, a deep understanding of the machinery, and even a supporting team, you likely wouldn’t even be able to start it.

“Vibe coding” or put more simply, chatting your way to working software, is truly miraculous. And it has enabled me to build features and tools in weeks, which would’ve taken me months, only last year.

But here’s the catch: to use these tools effectively, you need to understand the fundamentals more deeply than ever. You still need to work within constraints of your organisation. You still need to follow collaborative practices. And you still need to understand what makes software maintainable rather than just functional.

AI doesn’t replace this knowledge; it amplifies it. In the capable hands, it’s a force multiplier. In careless ones, it drifts into mimicry.

Where these forces converge…

These three forces aren’t separate trends. They’re interconnected aspects of a fundamental shift in how value is created in creative work. The question isn’t whether you'll be affected by this shift; you already are.

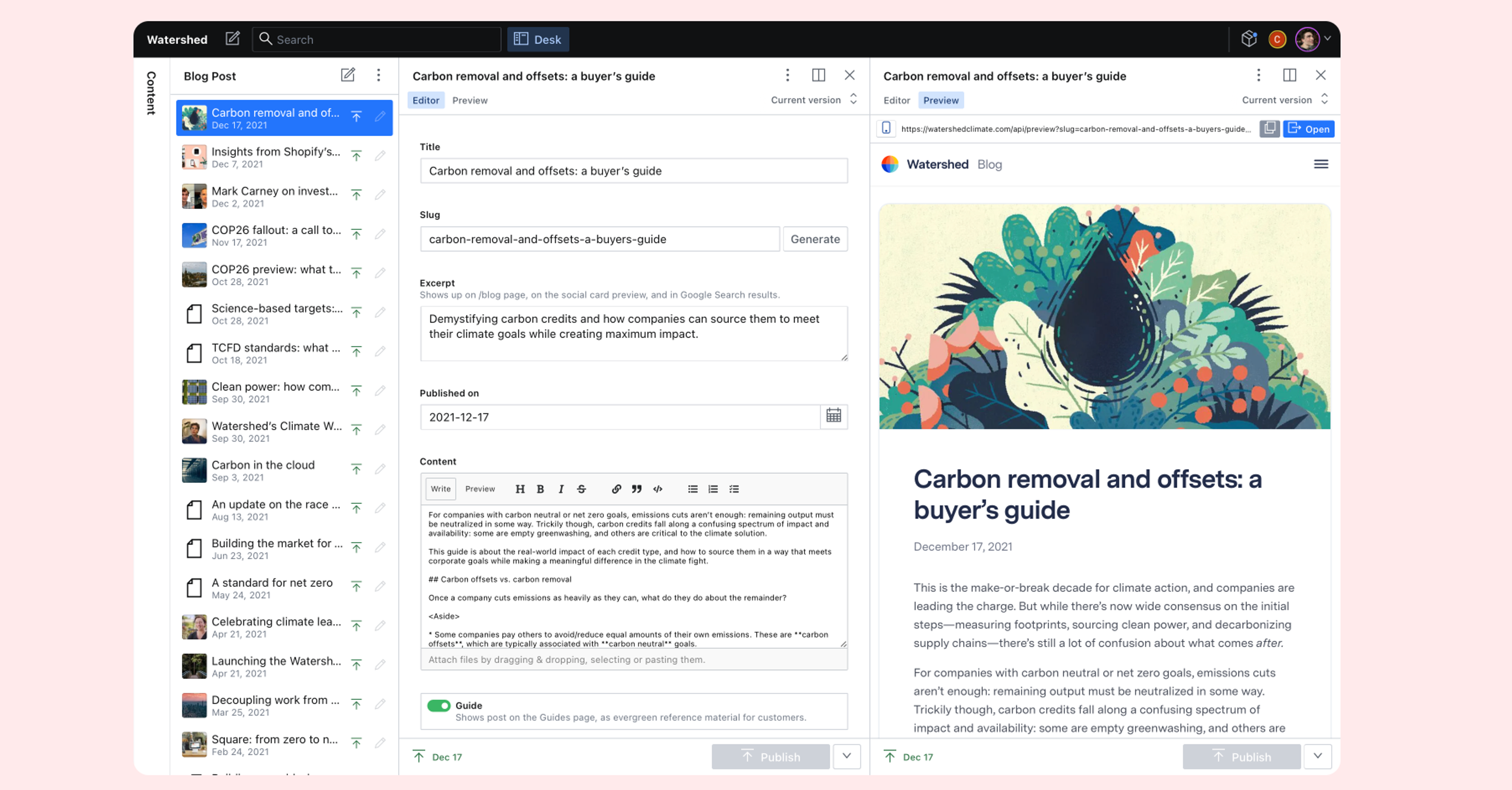

When I began writing about AI’s impact on design, I somehow ended up building my own text editor — AI included — that lets me audit the quality of my writing while still preserving my voice (British, self-deprecating, sarcastic, and forever distracted by the weather).

A year ago, this was beyond my technical reach. Today’s tools made it possible.

But knowing what to build, how it should work, and why it should exist (even if only to serve my whims), everything I’d learned to that point about design, product thinking, and the craft of building.

This is the new creative reality: we’re hybrid professionals, blending making and curating, execution and strategy, depth and breadth.

What this means for you…

So here we are, caught between roles that no longer exist and titles that mean everything and nothing. But, rather than resisting this transformation, embrace it as the most interesting professional development in decades. And here’s how:

- Start by auditing your daily tools versus your job description - I suspect you’ll find them misaligned. Identify which skills are becoming outsized in your workflow; those are worth doubling down on.

- Invest in developing your taste alongside technical learning - because one without the other is incomplete.

- Most importantly, embrace the identity ambiguity as a feature, not a bug - the uncertainty is uncomfortable, but it's also liberating. You’re no longer constrained by what your role is supposed to be; you’re free to become whatever combination of skills serves the problems you’re trying to solve.

The key insight from my three-month Figma hiatus isn’t that roles are disappearing, it’s that the best work happens when you stop worrying about what category you fit into and start focusing on what unique value you can create at the intersection of your converging skills, refined taste, and deepening tool mastery.

Just please, remember to open your design tools occasionally. They miss you, and so do I.