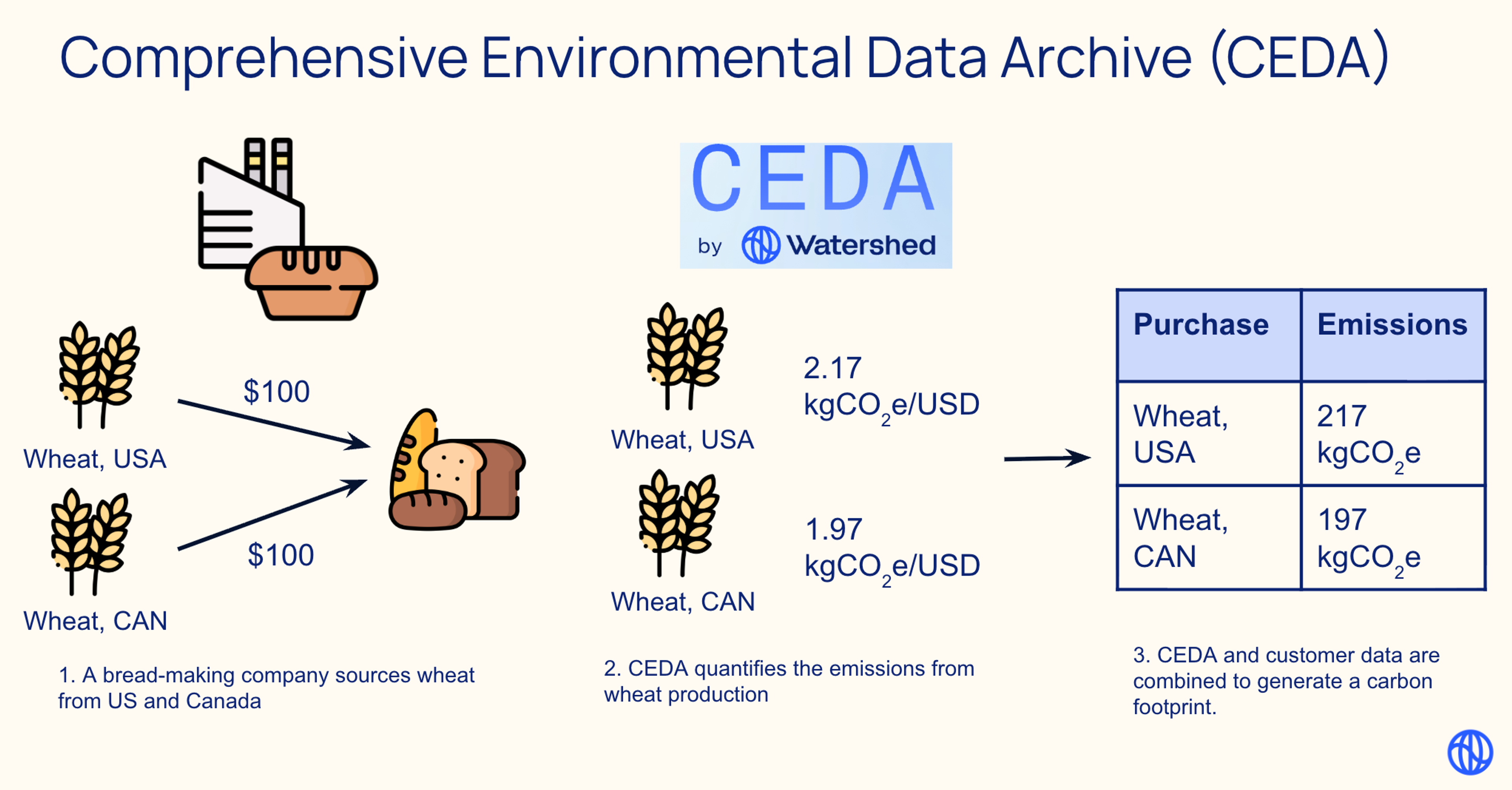

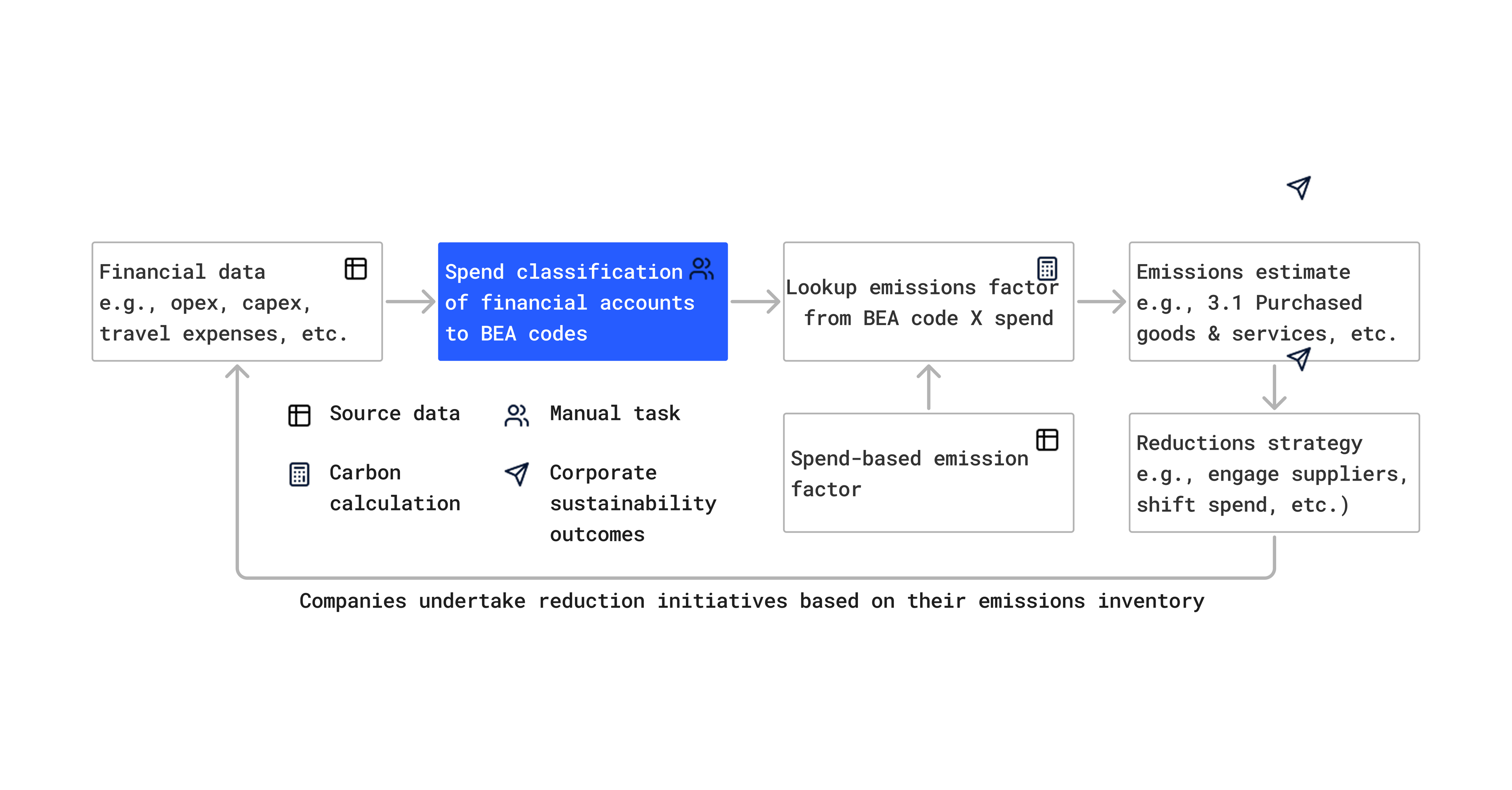

In 2025, Watershed launched two AI products: Product Footprints and Report authoring. Product Footprints uses AI to decompose supply chains by breaking down purchased products into component materials and processes, then calculating emissions at each step. Report generation uses a RAG pipeline to generate report responses from arbitrary input documents.

Both are multi-agent systems where specialized agents handle different stages of the pipeline, each with their own failure modes. There's rarely one correct answer in either product, but there are egregious errors a human would never make, and subtler ones that require expert judgment to catch.

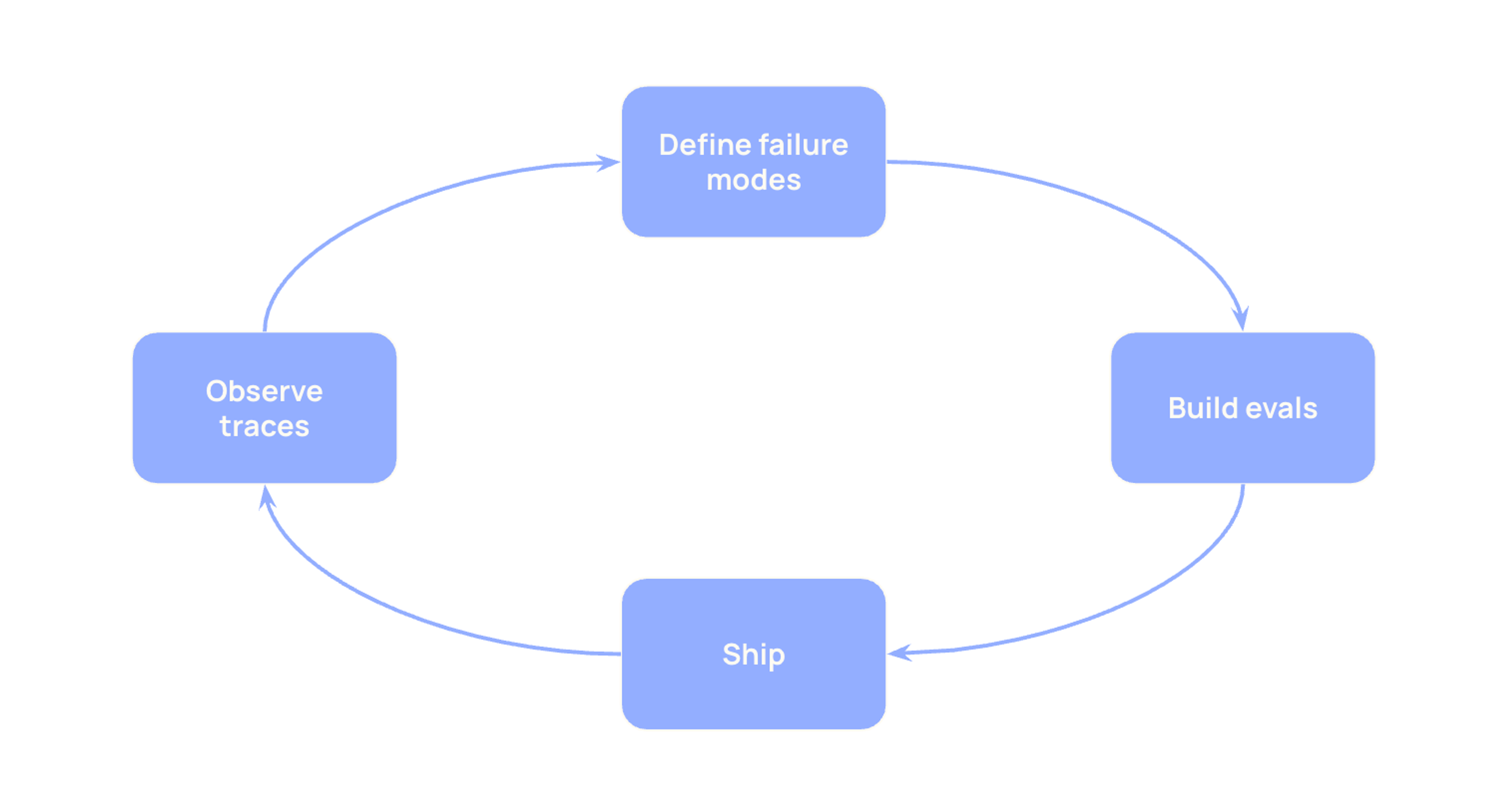

Our evals needed to catch those while letting us iterate fast on everything else. After months of iteration, we landed on a framework we now use when planning evals for new AI products. It distinguishes two kinds of evals, property evals and correctness evals, and provides a set of questions for deciding which to build and when.

Part 1: What you're evaluating

Property evals

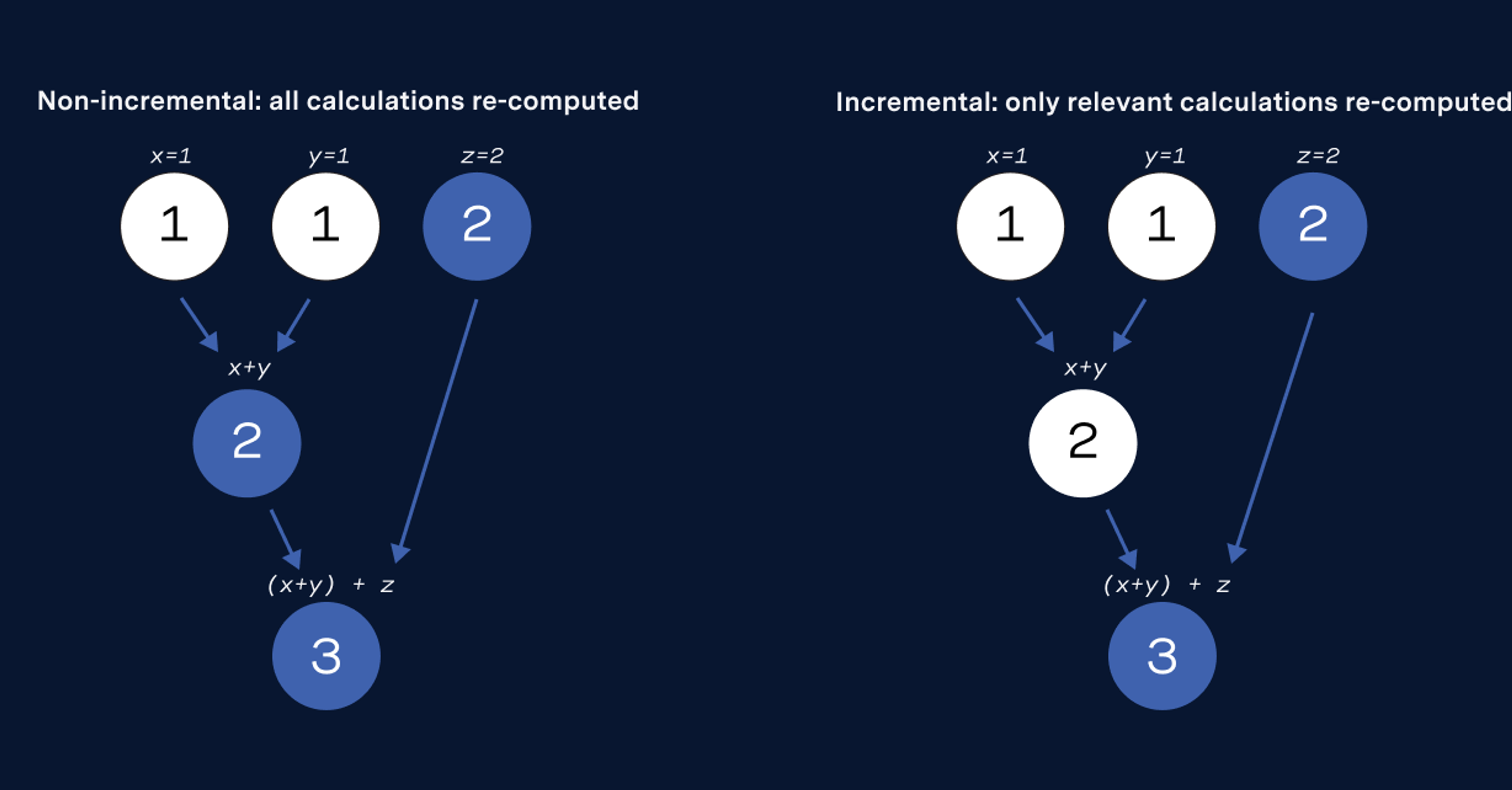

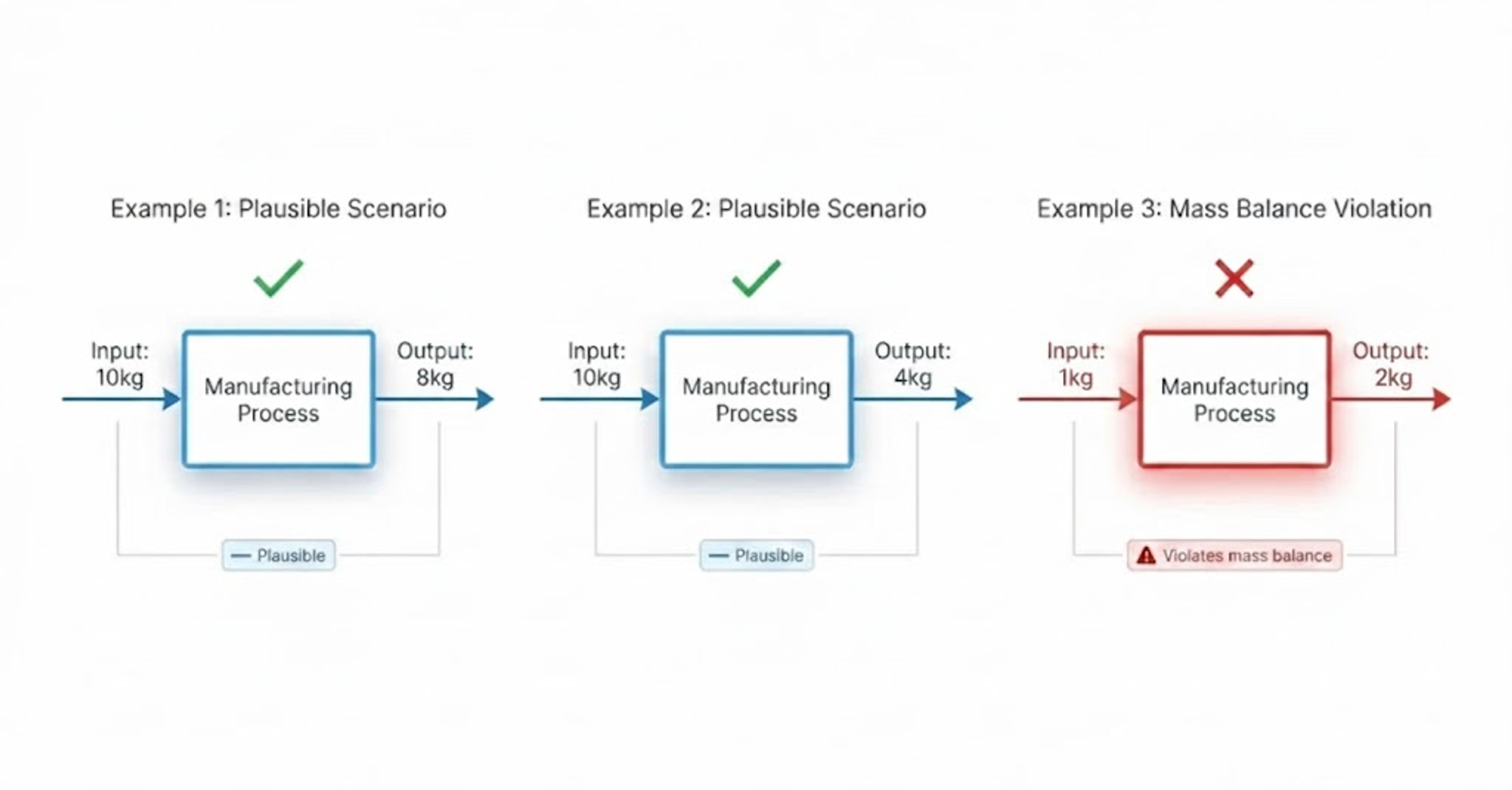

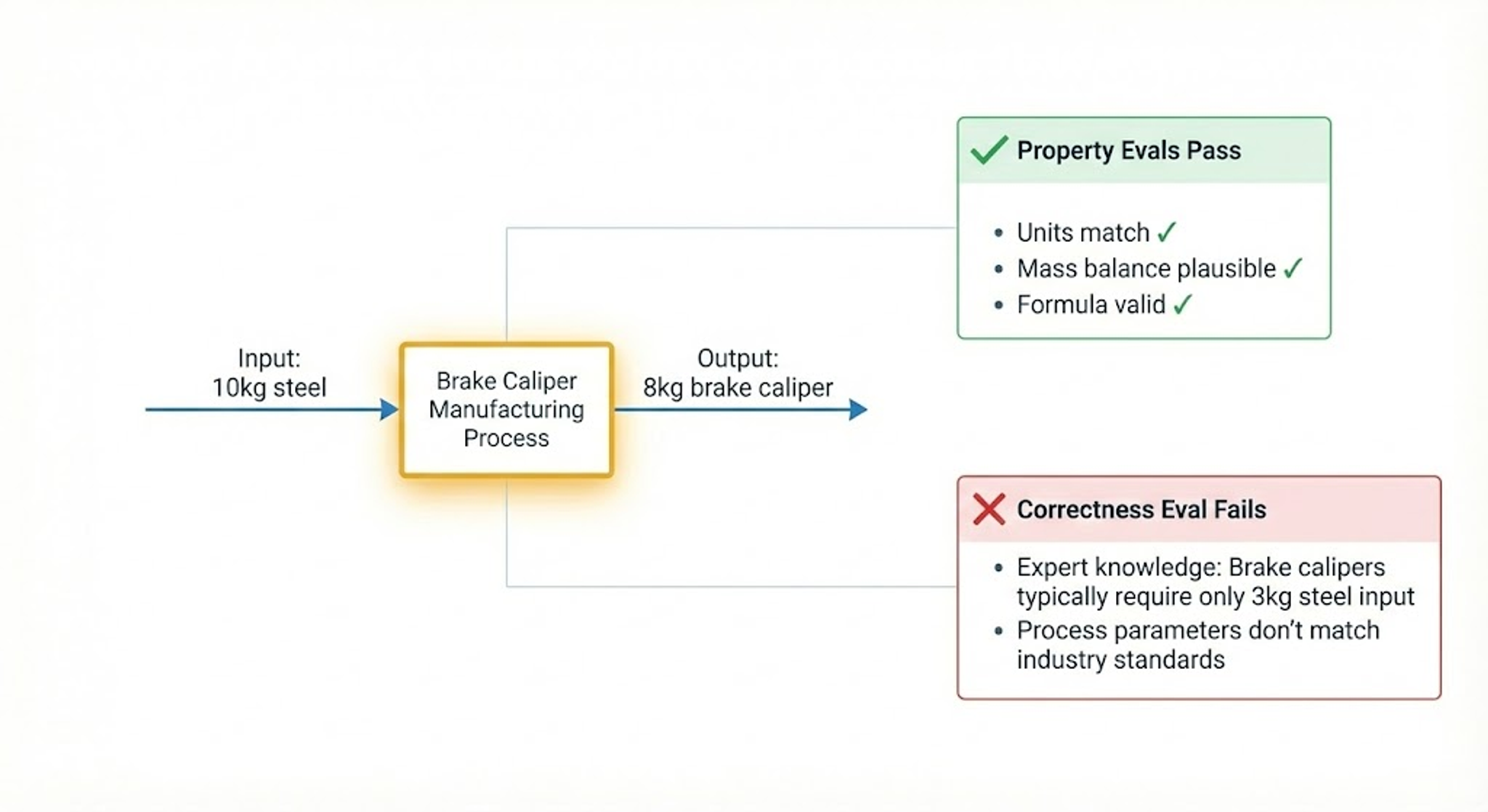

For any product footprint, there's rarely a single "correct" answer when deciding between the precise input ratios for the metal in a brake caliper or the amount of electricity used for machining down a kilogram of aluminum, but there are answers that are obviously wrong. A process where physically implausible amounts of inputs are required to produce a kilogram of output. A formula where the units do not align. These are errors a human expert would never make, and they can instantly erode user trust.

You can spot these errors without knowing the ideal answer. That’s a property eval. It asks: “does this output satisfy known constraints?” rather than “is this the correct answer?"

Definition: Input-agnostic checks that verify outputs satisfy quality constraints or invariants.

Examples:

- Formula validity: Are units dimensionally consistent? Are input/output ratios physically plausible? Are any of the division/multiplication signs flipped?

- Faithfulness: Does the output cite actual data sources (not hallucinated)?

- Format validity: Is the JSON well-formed against a schema?

Note: While property evals don't need input-specific ground truth, LLM-as-judge property evals still require eval datasets to develop/tune the judge and prevent regression.

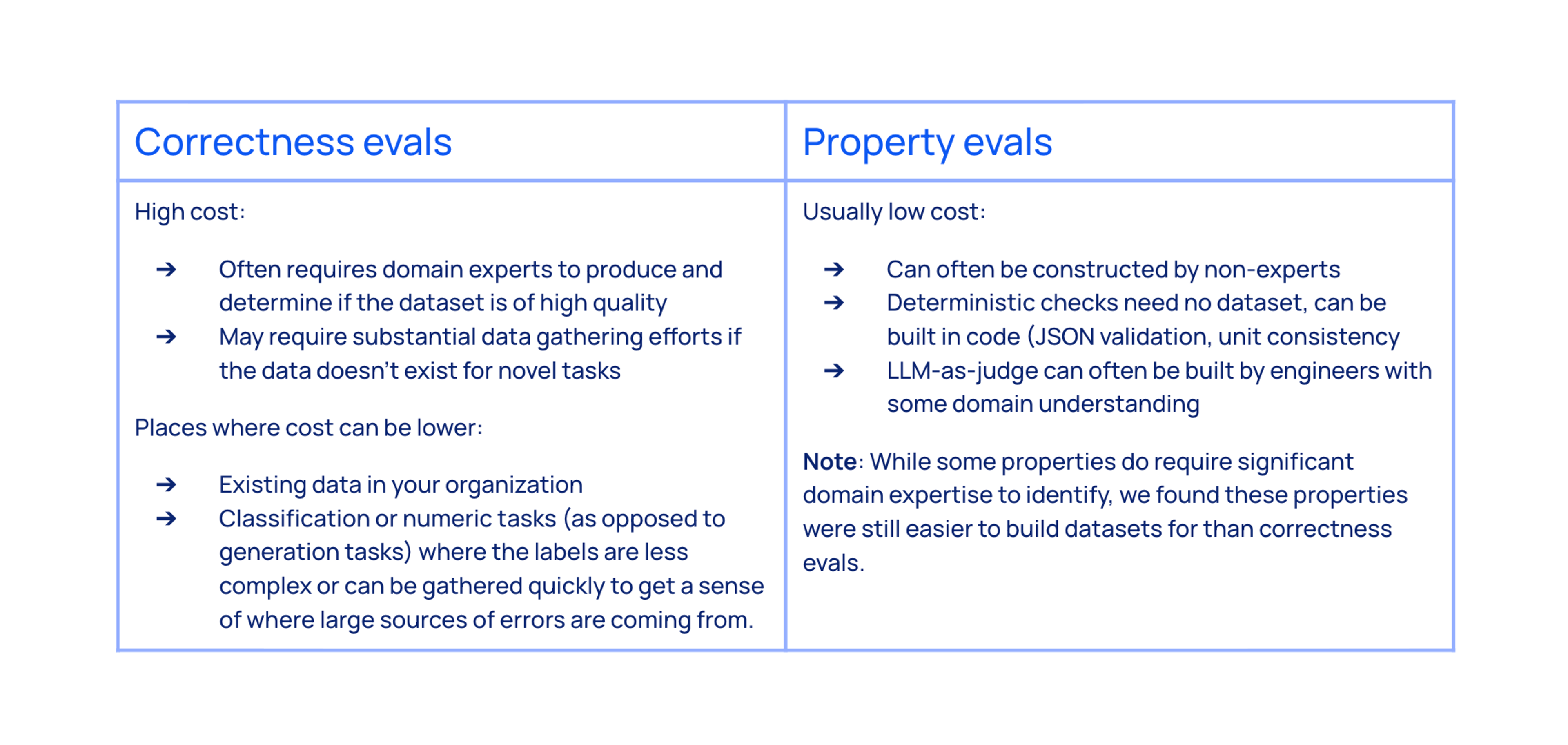

How we use this in practice: Each time we identify a new relevant property, we create a property evaluation to measure it. While it can require domain experts to identify useful properties, creating the dataset and implementing them tends to be less difficult. Wherever possible, we add the judge directly into our runtime to correct errors before they are shown to users.

Correctness evals

Property evals catch egregious errors, but they don't tell you if the system is actually producing the correct output. For that, you need evaluations that compare your AI-generated output against known correct examples—these are correctness evals.

Definition: Correctness evals compare system outputs against ground truth to verify accuracy. They answer "is this the right answer?" rather than "does this satisfy basic constraints?"

We found it helpful to think of correctness evals in two groups:

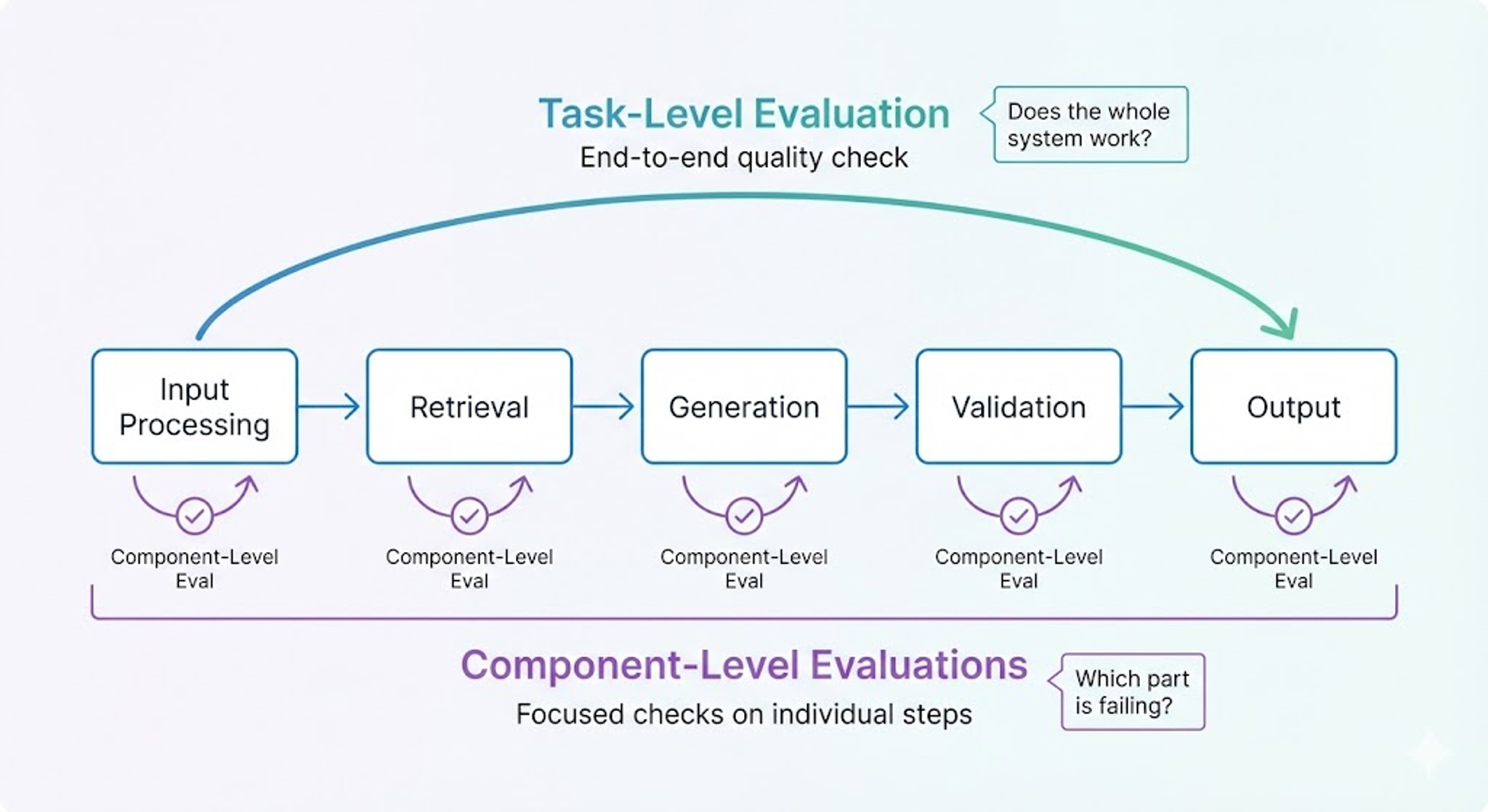

- Task-level evals measure end-to-end system performance. For Product Footprints, this means: given a product like "cotton t-shirt," does the AI generate a full supply chain decomposition and emissions calculation that matches expert expectations? We measure the % difference in the estimated kilograms of CO2 equivalents against a reference value.

- Component-level evals test specific parts of the system. When we saw large errors in our task-level metrics, we created focused evals for the problematic components. For example, we built a component-level eval for industrial energy estimation. It drove targeted improvements and caught regressions when changes elsewhere touched that component. These component-level evals let us iterate much faster and with more precision.

How we use this in practice: Task-level evals show overall system quality. When we see failures, we conduct an error analysis to identify which component is responsible. Then we build targeted component evals to iterate faster on that piece. Once the component improves, we re-run task-level evals to confirm the fix flows through. This layered approach is essential as the system grows in complexity.

Part 2: Three questions to help decide what evals to build

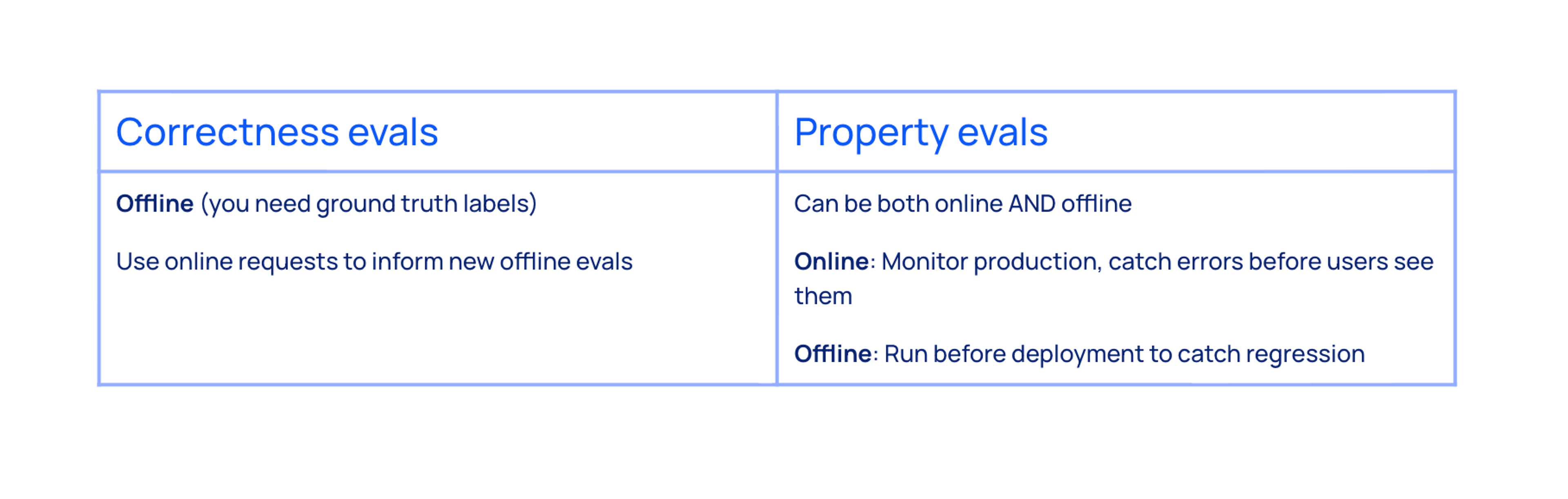

1: Can we catch this in production, or only in testing?

Our formula validity checker started as an offline eval. However, it soon became clear that this check did not need ground truth and would be a useful way to catch errors in online runs. So we deployed it as an online guardrail that catches errors in real product footprint calculations, while also running offline on logged outputs to build regression datasets.

Property evals are uniquely suited for this dual deployment. Correctness evals, by contrast, need ground truth and therefore are primarily offline.

2: How expensive is this eval to create?

Before LLMs, building an ML system meant starting with a labeled dataset, which meant a high upfront cost. LLMs flip this. You can ship a working system before you have comprehensive evals. The question becomes: which evals should you create and how does the cost of different evals affect which ones you should create first?

A good example of this comes from a different AI product at Watershed, our Reporting product. For our Reporting generation product, we needed to check whether generated report responses were supported by cited sources. "For each sentence in the report response, is this sentence supported by these cited text chunks?" An engineer does not require deep domain expertise to make this judgement. For this task, engineers built an LLM-as-judge, created a validation dataset, and iterated quickly. This freed up our sustainability experts to focus on higher-leverage work: validating whether reports were complete and correct, which genuinely required their expertise.

3: Is this eval truly representative of the customer problem?

As the the Report generation product matured, we discovered our customer input documents didn't match our assumptions. We built correctness evals based on one type of input format, but customers wanted to upload entirely different document types. Our expected answers were calibrated for inputs we weren't seeing in production, making the evals obsolete. Regenerating them would require domain experts to create new ground truth for the actual input distribution.

Property evals, by contrast, stayed relevant. "Is this claim faithful to its sources?" is a valid check regardless of how our quality standards evolve. The constraint, and the dataset and system that goes with it, will still be valuable even if our definition of "good” changes.

Deciding on the right evals for complex, ambiguous tasks can be challenging. Asking a few questions upfront can dramatically reduce your risk of overbuilding or testing the wrong things:

- Can we catch this in production, or only in testing?

- How expensive is this eval to create?

- Will this eval still be useful in 6 months?

The mental models of how and when to utilize different kinds of evals let us ship with confidence while our understanding of the problem evolved. We caught the errors that would destroy trust (unit mismatches, hallucinated sources, mass balance violations), while giving ourselves room to learn what "good" actually meant for our users.

The goal isn't a perfect eval suite. It's an eval strategy that grows with your system.