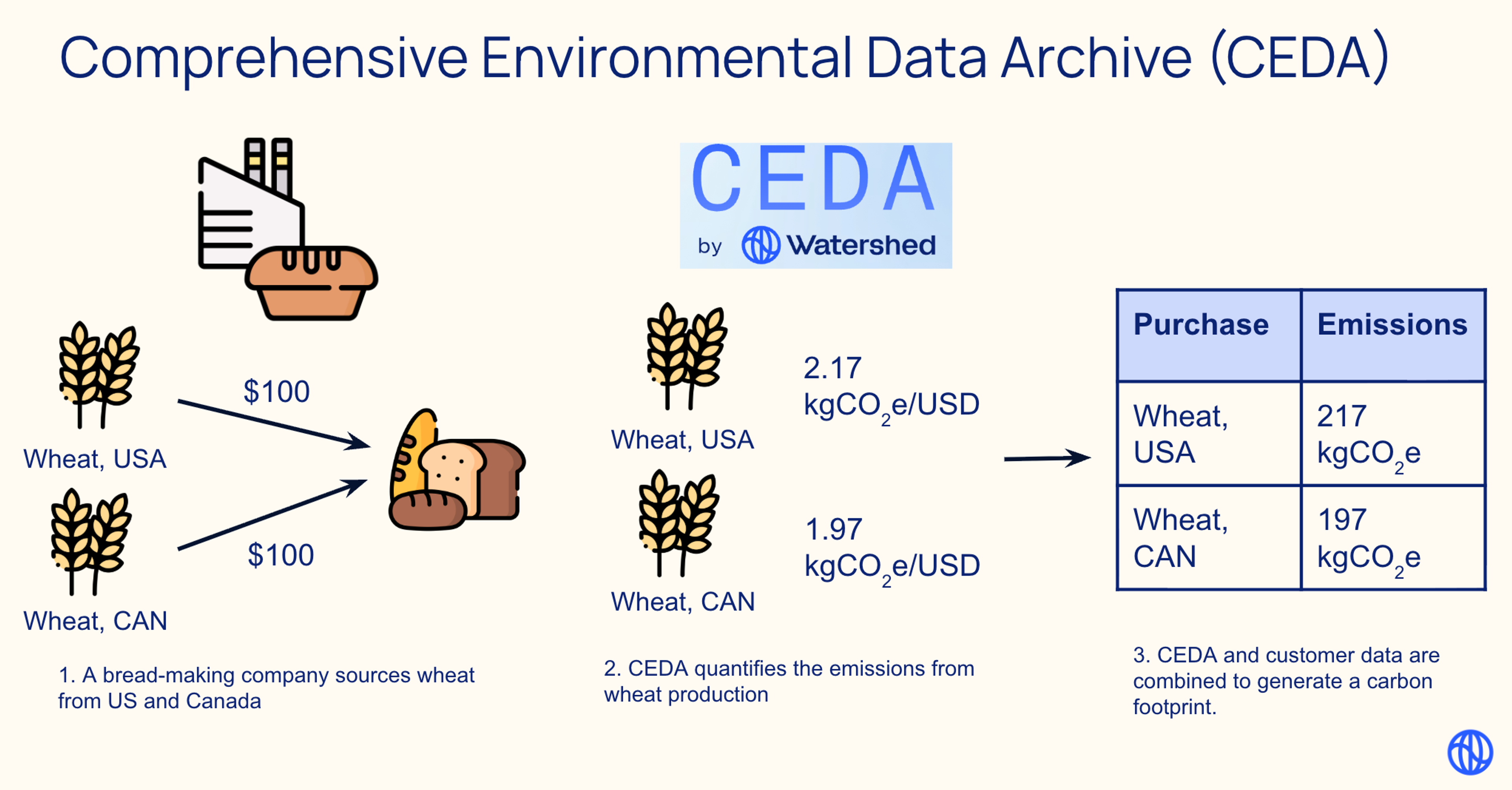

In 2025, Watershed built and launched an AI product: Report generation with AI. Report generation uses a RAG pipeline to generate report responses from arbitrary input documents.

When we first set out to build this system, it felt like the whole AI world was screaming at us "evals evals evals". Our instinct was to build comprehensive task-level evals: "Given a set of input documents, the generated report responses should contain points X / Y / Z."

We looped in the PM, brought in sustainability reporting experts, and tried creating an offline end-to-end correctness dataset. We floundered for a bit. Creating ground truth was painfully slow. Our input document types kept evolving as we learned from early users. Domain experts spent hours labeling datasets that became outdated within weeks. Each new document type meant regenerating eval datasets. We were stuck before we even shipped.

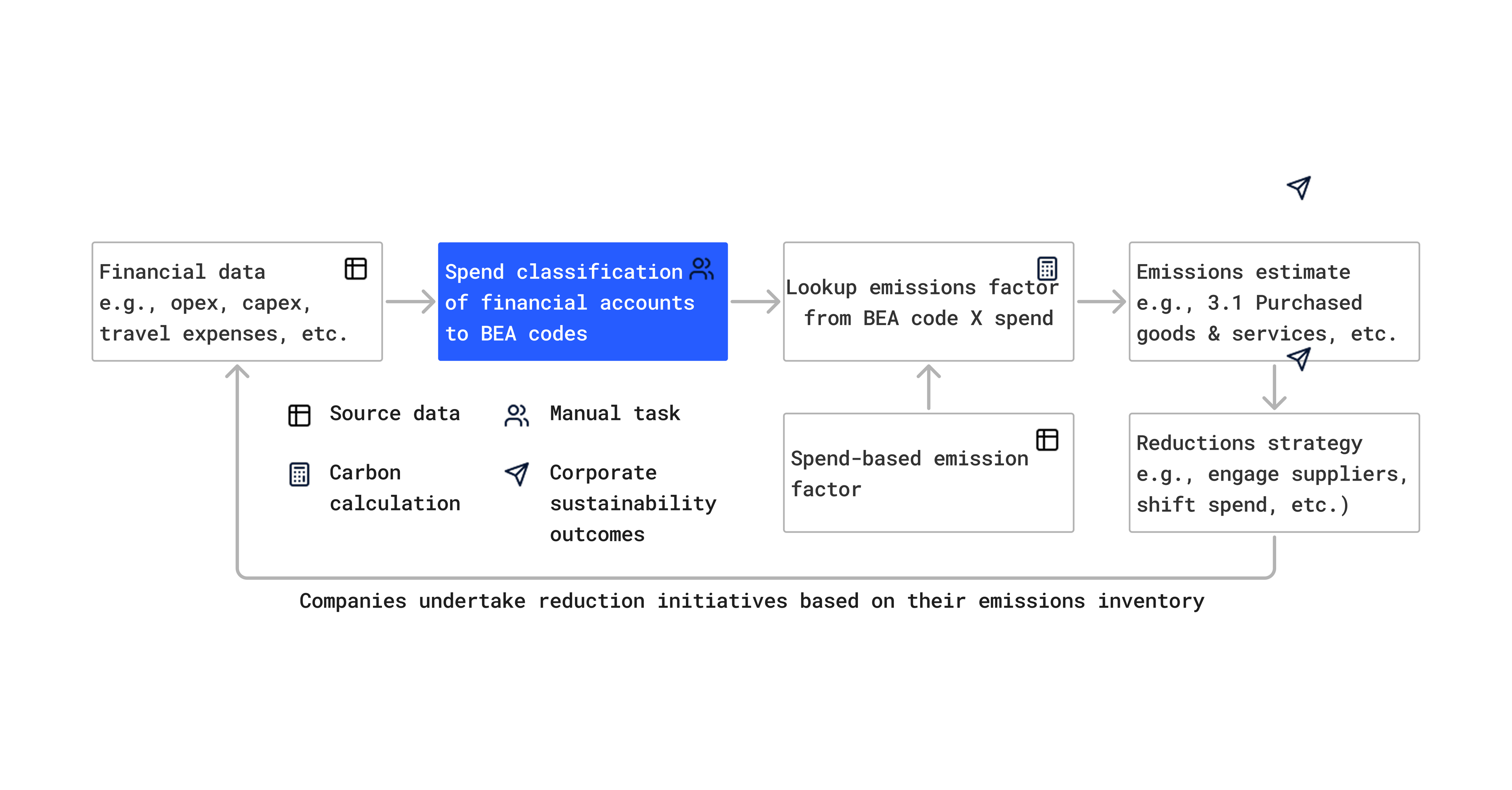

After months of iteration across multiple AI products (Watershed also shipped Product Footprints), we've learned that building an effective evaluation strategy is about not only the technical mechanics of evaluation, but also the team processes and product decisions that determine which evals to build and when. This post shares three critical lessons about the organizational side of AI evaluation that we wish we'd known from day one.

User needs and dataset creation burden heavily influence eval strategy

Building an eval strategy requires two critical things:

- A clear understanding of what "good" means. What does "correct" mean for your use case? What's the minimal quality bar for faithfulness, precision, recall? What would be catastrophic for your users? What are the failure modes that could expose them to regulatory risk, reputational damage, or stakeholder backlash?

- Realistic assessment of evaluation dataset creation capacity: How quickly can we create ground truth? How fast are our inputs evolving? Who is creating the evaluation datasets? What's the best use of domain expert time?

For Watershed’s regulatory reporting product, the catastrophic failure is hallucinated claims that customers might publicly report. The input documents also vary wildly, which compounds the challenge. So, we focused on property evals for faithfulness first (is every claim supported by sources?) because these evals were both the easiest to build and addressed our most critical concern. Engineers could build these without domain experts, they were resilient to changing input types, and directly prevented the #1 user fear.

How to apply this:

- Identify your catastrophic failure mode. What error would expose users to real risk? Prioritize preventing that over average quality improvements.

- Audit your eval creation capacity honestly. Who's building evaluations? How fast are your inputs evolving? What's the highest leverage area for your domain expert to evaluate?

- Once you have those, identify what kinds of evaluations might be the most helpful.

Eval strategy must be part of product strategy because, in many cases, the agent is the product. At Watershed, we're exploring different ways to integrate eval metrics into our product development cycle, such as gating milestones on eval clarity (prototype to beta requires defining catastrophic failures; beta to GA requires hitting eval targets) and including eval strategy as a required section in PRDs.

Evolving usage is hard to proactively account for, so don’t try too hard. Instead, make it easy to build evaluations from live examples.

You can't predict all input combinations upfront, so don't try. Build evaluations from real usage instead.

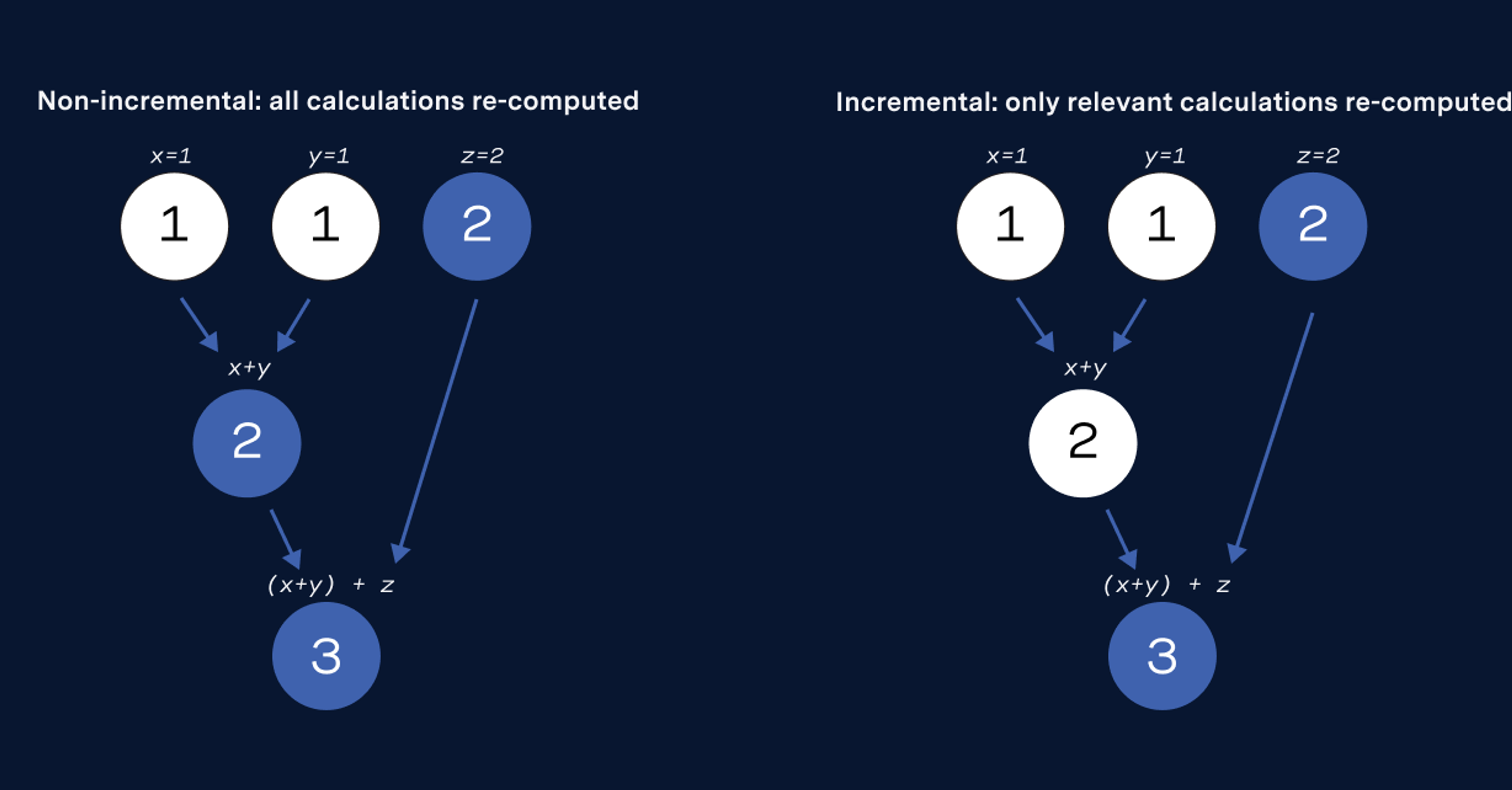

When initially building evaluations, our instinct was to build a comprehensive set that tested all combinations of input documents to ensure they produce expected outputs. This approach is manageable with 1 input document type, but breaks down with 20. We'd need to account for diversity within each document type, then test every possible combination - documents used alone, in pairs, in groups of three. Worse, each time we discovered a new document type, we'd need to create entirely new input/output pairs to test against all existing combinations. The eval maintenance burden quickly becomes infeasible.

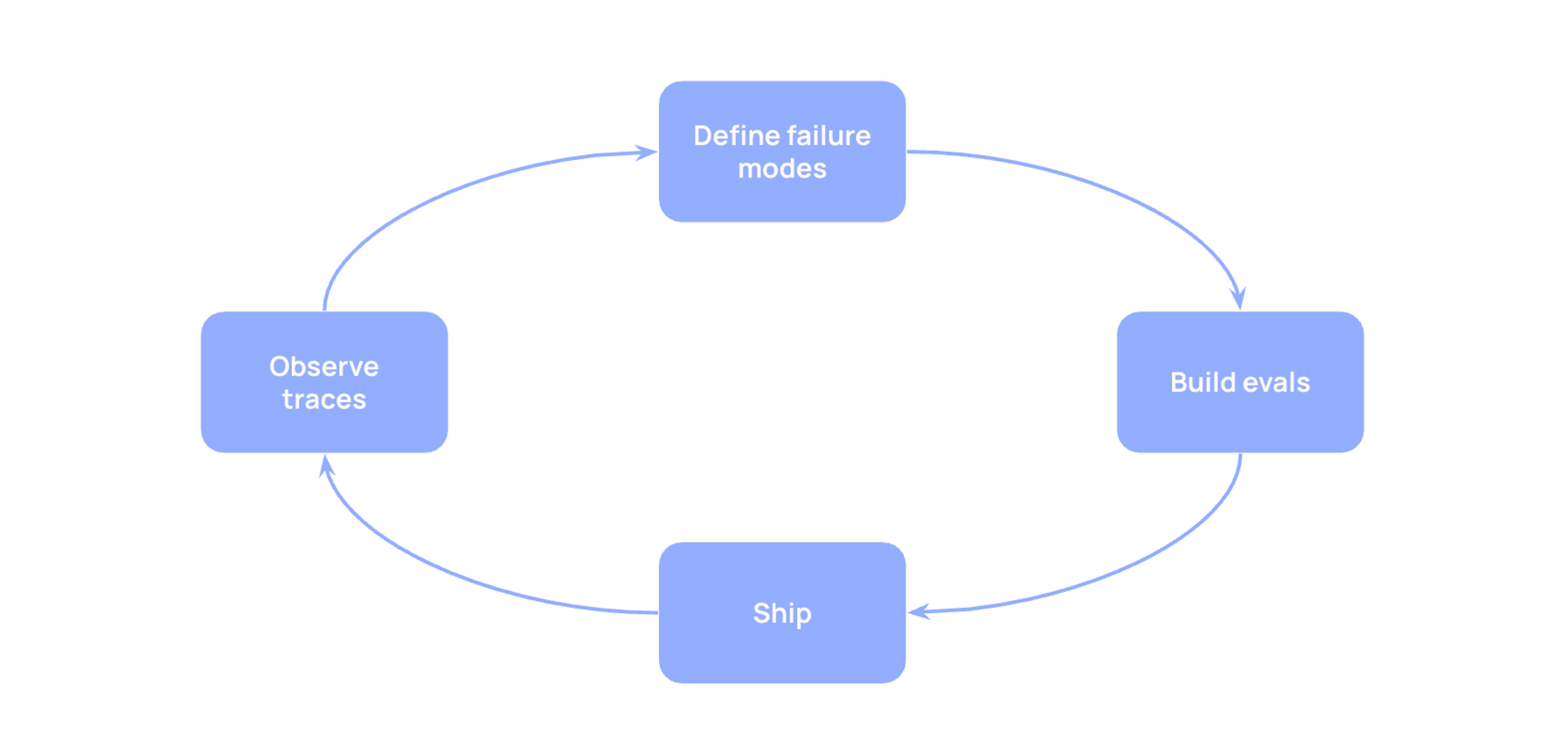

Instead, in both Reporting and Product Footprints, we shipped a prototype to development partners with minimal evals, then used production traces to identify errors and therefore what to eval next. This allowed us to ship quickly while ensuring our evals maintain a distribution of inputs similar to actual usage/issues.

How to apply this:

- Ship with the minimal set of evals needed to maintain user trust and set clear expectations about system quality

- Enter the feedback loop as soon as possible: look at traces, analyze them, and incorporate findings into your eval dataset

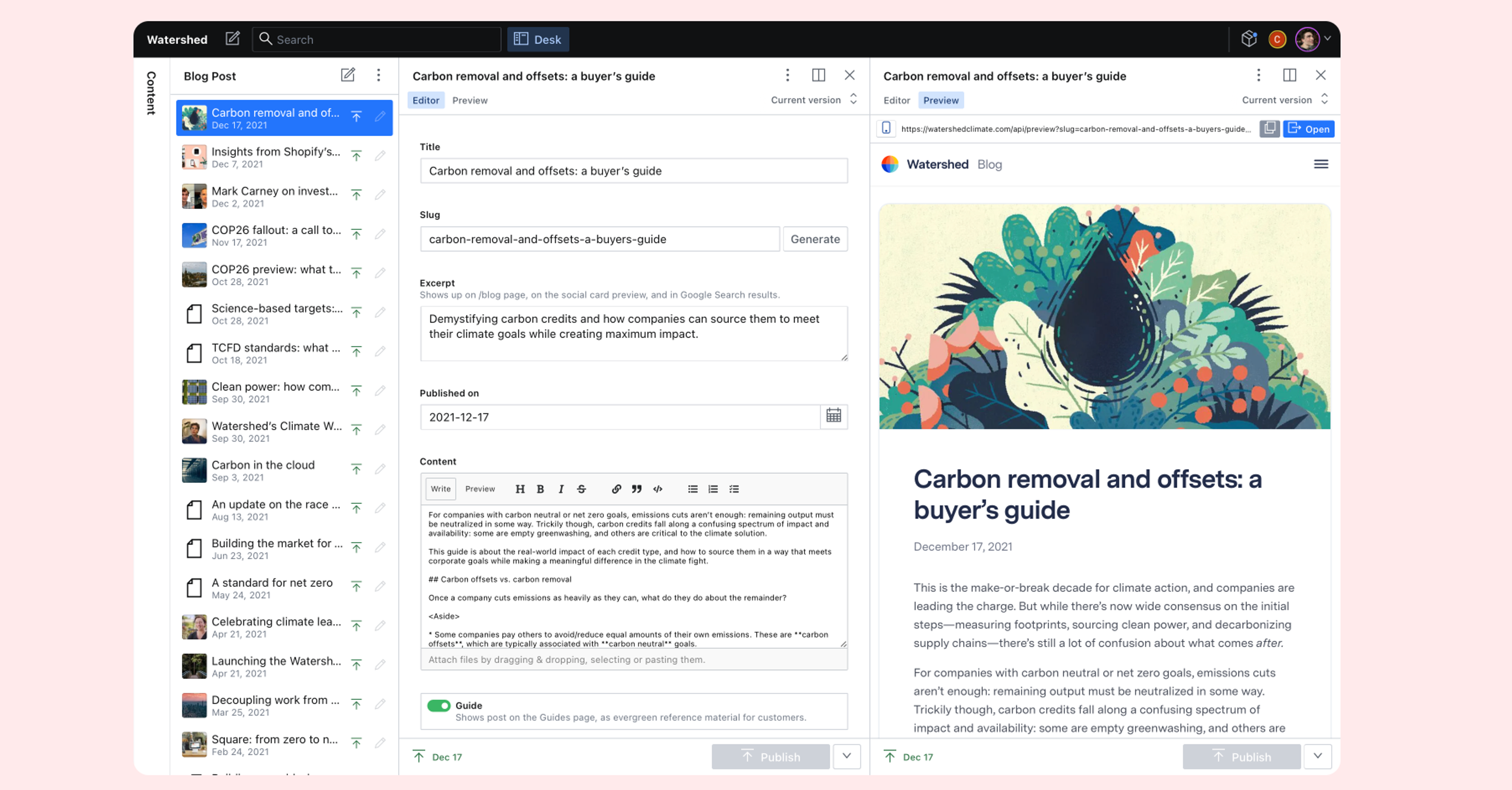

- Invest in tooling that makes this loop fast. The faster you can go from "I saw this bad trace" to "I have an eval for it," the faster you can iterate with confidence

The key is building your AI product to be tolerant of shipping, learning, and iterating. Accept you won't catch everything before launch. The goal is rapid learning and iteration, not perfection upfront.

One person MUST be responsible for quality iteration

Someone must own AI quality. Specifically, someone must be responsible for (a) looking at traces, (b) annotating, (c) translating to eval datasets, and (d) explaining problems to the team. Hamel Husain proposes one person - a benevolent dictator who "becomes the definitive voice on quality standards." We’ve found this advice useful.

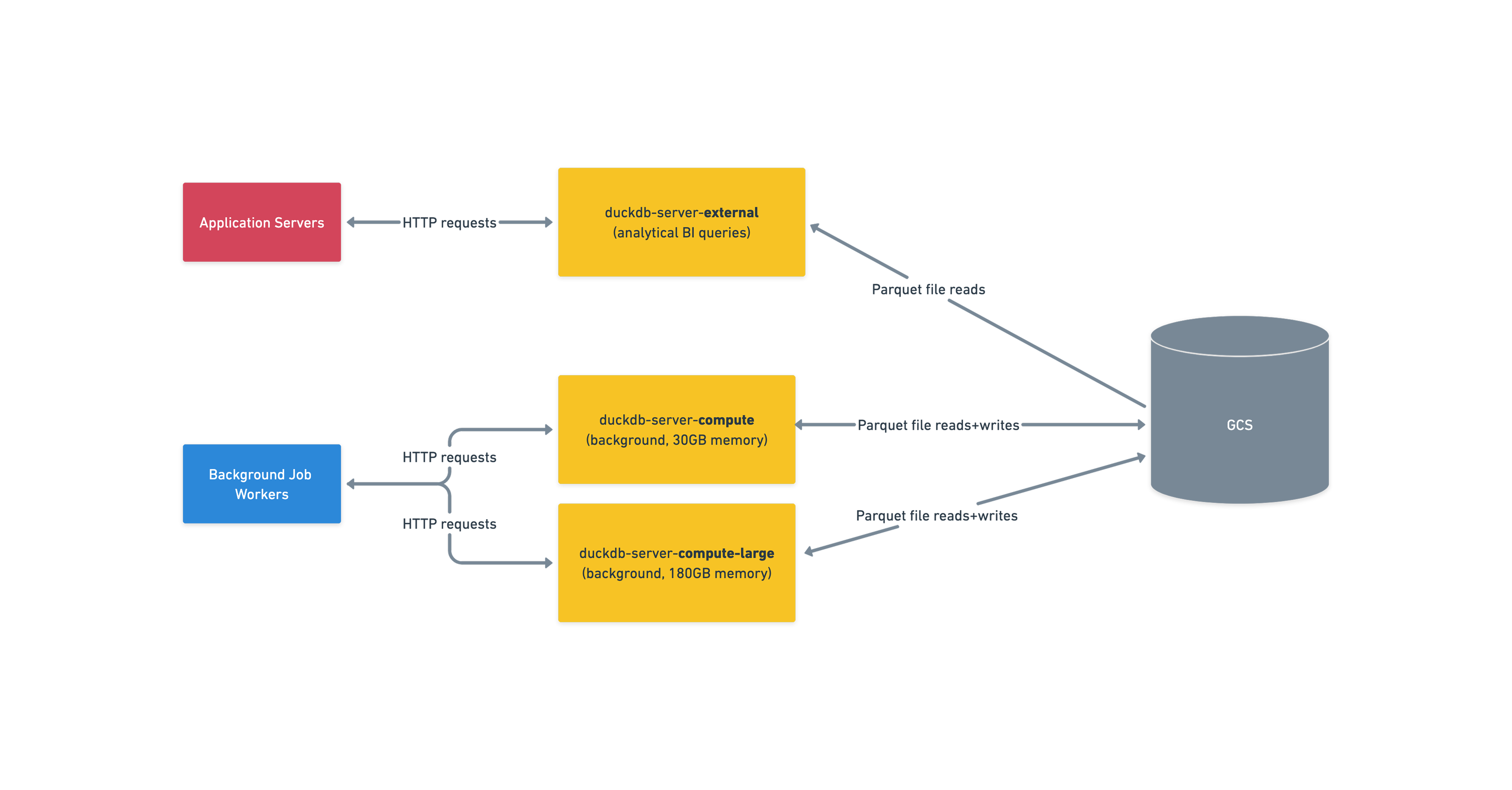

At Watershed, AI product development changed how we observe - from video analytics (Fullstory) and aggregated statistics (Mixpanel) to trace platforms (Langfuse). In our Product Footprints team, we assigned this “benevolent dictator” role to an engineer (though traditionally this might be a PM). This person reviewed traces, translated errors to evals, and communicated issues to the team, keeping everyone grounded in real product behavior and focused on problems users actually faced.

How to apply this:

The person responsible for AI quality doesn't initially need to be a domain expert, but they certainly need to become one. What matters is intentionally assigning this role.

If they're not a domain expert, they need: (a) training or regular access to someone with domain expertise, and (b) dedicated time in their role to review traces.

If they are a domain expert (and not an engineer), present traces in a digestible format that makes annotation easy. Then process those annotations to identify patterns, which become your next tickets. We've found it helpful to build small apps (using AI) that streamline this review process.

This ensures you maintain a constant pulse on product quality, domain expertise grows within the team, and engineering resources focus on the highest-value problems.

Build evals you can sustain. When we started building AI products at Watershed, we thought the hard part would be the technical mechanics of evaluation. It wasn't. The hard part was figuring out what to evaluate in the first place, how to keep improving without drowning in eval maintenance, and who would actually look at the results.

We learned that evaluation strategy is fundamentally a product decision. It forces you to define what quality means and what failures you're willing to tolerate. That alignment between product and engineering has to happen before you write a single evaluation, because the evaluations you build become the product you ship. Then, you can't predict everything users will need upfront, so build the minimal evaluations that maintain trust, ship, and let real usage show you what to build next. And crucially, someone needs to own that quality bar day-to-day, turning traces into insights and insights into improvements.